GUEST BLOG: What does it look like to die well? To grieve well? The COVID-19 pandemic has stolen the opportunity from many to die or grieve as they would have wished.

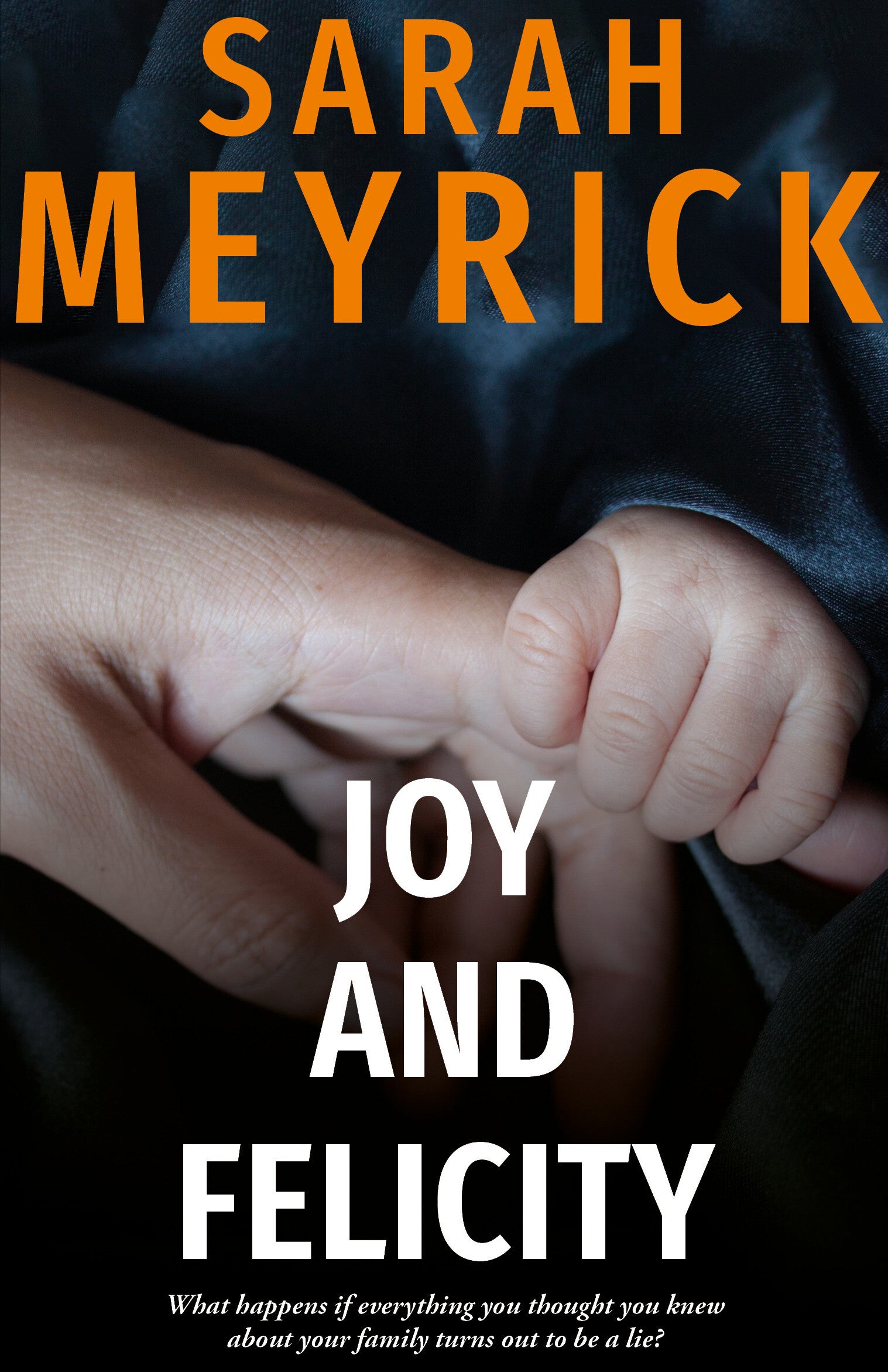

Author Sarah Meyrick reflects on the themes of forgiveness and dying well in her new novel Joy and Felicity and on her own personal experiences with grief, both before and during the pandemic.

One of the things that has been so painful during the pandemic has been that many of us have been denied the chance to say goodbye. It’s been agony for families not to hold a loved-one’s hand in their last hours. It’s been horrible to not to be able to attend our friend’s funeral. Think of the poor Queen, sitting all alone, distanced from her family at the funeral of her husband of 73 years. She was the picture of lonely dignity.

I was lucky. My mother died in February 2020, with her family at her bedside. She died literally a few seconds after the fifth grandchild arrived to say goodbye. We had the most wonderful funeral packed with more than 160 friends, family and neighbours. We ran out of mugs for tea at the reception. But it was wonderful to share memories and laughter and tears and hugs as we celebrated her extraordinary and beautiful life. As we honoured her.

In retrospect this seems even more extraordinary as just a couple of weeks later the UK moved into the first lockdown. Our grief continued, of course, but what a difference it made that we’d had the chance to say a proper goodbye to her. These tried and tested rituals – a funeral followed by a wake, in our culture – have evolved over the centuries. There are variations to the pattern according to personal beliefs and character, but broadly, there’s an established way of doing things. Comfort can be found in the familiar rituals when we’re all at sea.

And they work. I don’t mean anyone waves a magic wand and everything is suddenly all right. Of course not. Grief is hard work. It takes as long as it takes. But almost everyone I meet seems to have a story about the difficulty of grieving in a pandemic. For me, there was a dear friend whose funeral was necessarily very small. A group of her friends planned to sing a memorial service for her in June. When it was cancelled, I was heartbroken. Unfinished business remains. The pandemic has shown – in so many ways, large and small – quite what we miss about our ordinary lives. The ‘old normal’.

Is it odd that I’ve found myself writing a novel about a dying mother over the last year? Probably not, although I will confess I’d conceived the idea long before my mother’s dying. Some of the ideas in it are about what constitutes a good death. How do we ease another’s passing? How do we let go of someone we love?

One of the central characters in my book, Felicity, makes it her profession to help people die well. She becomes a thanatologist: a therapist who specialises in accompanying people on their final journey through music and song.

If you haven’t heard of thanatology you are not alone. It is practised much more in the US than the UK. But many years ago I stumbled across the story of a harpist who was playing for dying patients in a Welsh hospital and have been fascinated ever since. It’s not simply a matter of playing music that is somehow soothing. A trained thanatologist can ‘tune in’ to a person’s condition and help slow their heart rate. Increasing numbers of academic studies have shown that a skilled thanatologist can make a measurable difference in calming a patient’s distress and easing their dying.

Felicity ends up accompanying her mother’s final journey on the harp. Her sister Joy, who is cut from more sceptical cloth, joins the vigil at her bedside. Both sisters need to make peace with their mother and each other, a thread that runs through the novel and binds the story. My hope is that the reader will feel a sense of resolution in the ending.

A friend of mine has asked me why I have written about death in each of my novels. Another points to the recurrent theme of love and loss. Fair enough. I’d just add forgiveness to the mix of themes I can’t leave out. At some level, it feels as if these are the only questions that matter.

I think that goes back to my own experience as a reader: the novels I enjoy most as a reader are those that transport me to another world. The ones that stay with me because I have understood a different point of view, become involved with a character – not necessarily liked them but empathised with them, cared about them.

I enjoy a book that leaves me not just entertained or amused, but having learned something, shifted in my understanding, seen something from an unusual perspective. Above all, had my emotions engaged. Which means that, somehow, I have understood the human condition a little better. Best of all, had a glimpse of grace and truth.

I hope I don’t lecture. As a reader, I don’t like being told what to think. As a writer, I’d rather raise questions than answer them. You’ll know, I’m sure, that famous Emily Dickinson poem:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth's superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

The Truth, she suggests, is too big, too bright, too dazzling to comprehend face on. Many people read that poem as referring to religious truth, as in: I am the way, the truth and the life.

Stories and music and art and creativity can help us find our way towards Truth. The slant approach is very appealing: I love that idea of the light breaking in sideways, at an unexpected angle. Sometimes truth emerges when you least expect it.

We don’t always get the death we would wish. Some of us will have witnessed a distressing end for those we hold dear. Or have a haunting sense of betrayal that we weren’t there when we should have been. That’s acutely painful.

But if my novel helps anyone think about what dying well means, particularly now in 2021, I’m glad. If anyone ends up pondering where forgiveness may be needed, so much the better.

Sarah Meyrick studied Classics at Cambridge and Social Anthropology at Oxford which gave her a fascination for the stories people tell and the worlds they inhabit. Her working life includes journalism, PR and running a literary festival. She lives in Oxfordshire with her husband. Joy and Felicity is her third novel and follows Knowing Anna (2016) and The Restless Wave (2019). Get your copy here!