Aristocratic Archbishops: exploring the life of Edward Vernon Harcourt

Added about a year ago by Tony Vernon-Harcourt

Family history is a popular hobby for many, but what if one of your ancestors was the last aristocratic Archbishop of York? Tony Vernon-Harcourt writes about his journey of discovery wondering what his great-great-great grandfather was really like

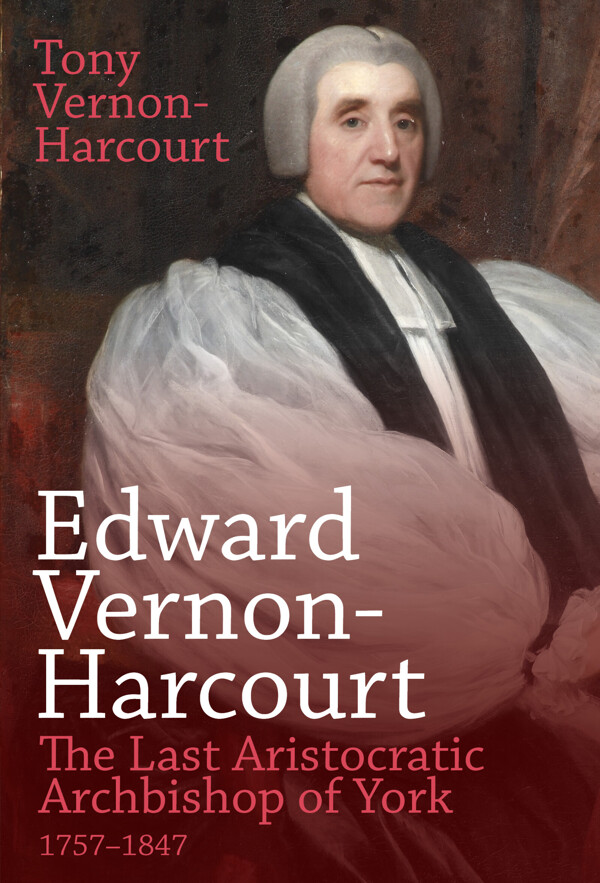

A marble bust of Edward Vernon-Harcourt, Archbishop of York from 1807 to 1847, had pride of place on the sideboard in my parents’ dining room. An engraving of a portrait of the Archbishop hung in the downstairs cloakroom. I had been told that he had had 16 children by his wife Lady Anne Leveson Gower and that we were descended from his fifth son. However, like most young people, I was not particularly curious to know more.

Some 50 years later, as retirement loomed, I decided to investigate my family history. My first book looked at the life of a great-great grandfather on my mother’s side of the family. Archibald Sturrock was an engineer, who designed the locomotives for the opening of the East Coast main line from London to York. With this project completed, I turned my attention the life of my Archbishop ancestor.

My initial investigations indicated little had already been written about him. A 1967 article in a church history magazine suggested he had been more interested in the wealth and privileges attached to his office than to the development of the church in Yorkshire. By contrast, the entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography stated he was a hardworking bishop, who helped the Church of England to adapt to the changes of the 1830s and 1840s. Both views could not be true.

My task was made easier by the work of one of the Archbishop’s grandsons, another Edward Vernon-Harcourt, who had examined the Harcourt family archives and transcribed the letters he found most interesting. He added some brief commentary. Privately printed towards the end of the nineteenth century, Volume XII of the Harcourt Papers included letters to and from the Archbishop and his wife, plus lists of his wife’s family members and their 16 children. All the archive was to be found in the manuscript department of the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

A second major source of information were newspapers. When I wrote my first book of family history, the only way to read historic newspapers was to visit the British Library in Colindale in London and flick through the pages hoping to spot something relevant. Now most newspapers are available online and can be searched for free in a local library or for a small charge online at home. There were over 20,000 references to the Archbishop of York between 1807 and 1847. The newspapers provided a remarkably full record of both his professional and social life. I was able to learn whom he invited to dinner and what the press thought of the way he voted in the House of Lords, and about the time he spent visiting churches around his huge diocese. Such research would have been impossible even ten years ago.

The third significant source was the Clergy of the Church of Egland database. Launched in 1999, it brings together clerical career records from some 50 archives for the period 1540 to 1835. It enabled me to find out who the clergy were who were mentioned in the Archbishop’s correspondence and find out how he used his right to appoint clergy to some 50 parishes in the diocese. Nepotism was accepted practice in those days, and I could, for example, check how he manged to move his three clerical sons to progressively better remunerated parishes.

Perhaps the task I found most difficult was to understand the politics of the first half of the eighteenth century. Bishops were political appointees. Political parties were not clearly defined as they are today. The Archbishop found politics difficult too. His father-in-law who helped secure his first promotion to Bishop of Carlisle, was a Tory but most of his friends were Whig sympathizers. He tried to avoid taking sides in politics unless the issue related to the Church. He considered dealing with his clergy more important than his political responsibilities.

Perhaps the task I found most difficult was to understand the politics of the first half of the eighteenth century. Bishops were political appointees. Political parties were not clearly defined as they are today. The Archbishop found politics difficult too. His father-in-law who helped secure his first promotion to Bishop of Carlisle, was a Tory but most of his friends were Whig sympathizers. He tried to avoid taking sides in politics unless the issue related to the Church. He considered dealing with his clergy more important than his political responsibilities.

The project also gave me an excellent excuse to visit several archives. The British Libray holds many letters between the Archbishop and various politicians. The Borthwick Institute in York contains records of his archiepiscopate. It was a pleasure to visit Gloucester Cathedral Library and establish what his role had been as a prebendary of Gloucester. Sadly, due to Covid, I could not visit all the archives I had hoped, but archivists at Christ Church and All Souls Colleges at Oxford, at Durham University, and many others were kind enough to help by emailing me photocopies of relevant records.

Drawing all the information together was complex. I decided that, when it came to his 40 years as Archbishop of York, a chronological approach would not be suitable. Every year his general pattern of life was the same. Whenever the House of Lords sat, he was expected to be in London. At best, he would spend about two to three months in the summer in his diocese and another one to two months over Christmas. I therefore looked at different aspects of his life separately, including, for example, his time spent around his diocese, his interest in music, his approach to pluralism and non-residence and his involvement with royalty and politics. Did you know it was once illegal to sing hymns in Book of Common Prayer services? This was one of the issues Archbishop Harcourt had to deal with.

Seeing the book in print after nearly ten years of research has been very satisfying. Hopefully it may inspire you to undertake research into your family. It is surprising how much information is available even for individuals who have not achieved the high office my ancestor attained.

Edward Vernon-Harcourt: The Last Aristocratic Archbishop of York is available now in illustrated hardback and e-book from Sacristy Press and all good independent book retailers.

Please note: Sacristy Press does not necessarily share or endorse the views of the guest contributors to this blog.