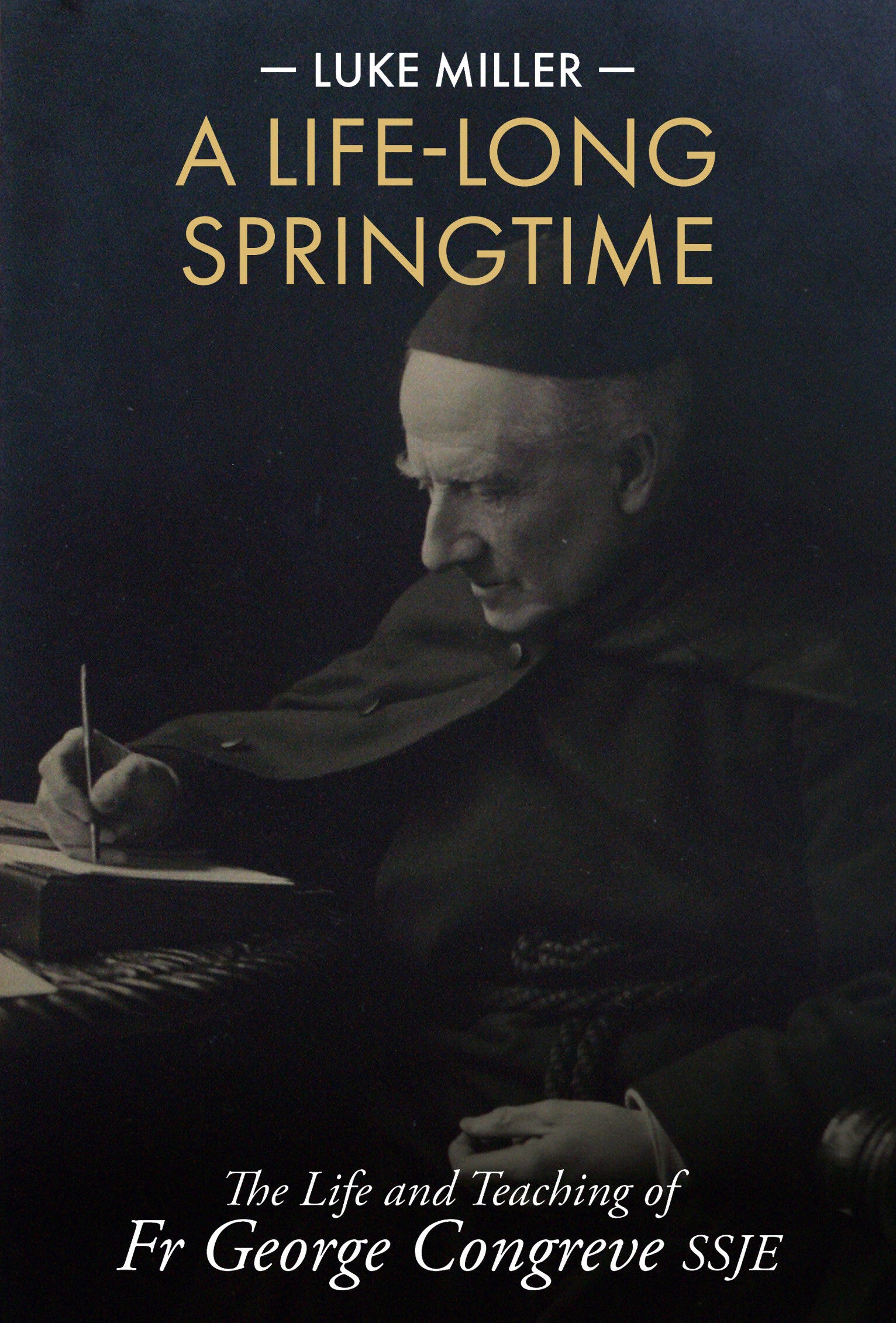

GUEST BLOG: Luke Miller, author of our recent release A Life-Long Springtime, introduces us to Fr George Congreve’s wisdom about transforming the disappointment that can often follow the holiday season into joyful hope in God and expectation of the future.

“After the holidays as we get into harness again, our thoughts naturally stray back to the blessed days or weeks left behind, and ask what treasure have we got out of the good time, what have we to show for it?”

So Fr George Congreve (1835 – 1918), began a reflection on holidays with how it feels to come back to the daily round. This January perhaps this is even more true, since even for those who have been able to have a break, the hope of the holiday crumbles into the renewed uncertainties of the continuing Pandemic.

Congreve was a masterful spiritual theologian and his reflection – as so often with his writing - has a remarkable contemporary application. Echoing Augustine (“Our hearts are restless till they find their rest in Thee”), Congreve points out that the human desire for holidays, our “impatience with worn out circumstances,” is a sign of our yearning for God. The “universal craving of our spirit for some change, [is] not mere idleness, but a witness to a divine purpose, and to our great destiny … The promise, ‘behold I make all things new,’ is anticipated in the very structure of human nature”

The impulse to holiday is “the awakening of the sense of its own greatness in a new born soul, and the seeking of its source in God.”

This means that to approach a holiday simply as an experience of travel or a time-off is to find that “our furlough does not always bring the happy time we expect.” A holiday is only satisfying when it is pointing beyond itself to God, “when we know that every new sight or sound may hide some new treasure of the eternal beauty and joy of God for us to discover, for our own refreshment and for the cheer of others.” The sense of holiday ended is then transformed from a lamentable regret to a continuing joy:

The Christian does not mourn holidays ended; He lives upon the good time afterwards through the working days that follow, and, as it makes his past sweet with thankful remembrances, it makes his future rich in expectation… Holidays left behind have an element of regret, but carried on to God in our thanksgiving they grow richer, the fields and the rivers gain significance, for God is making all things new for us, and we raise them to the level of our relation with himself in the Lord.”

For Congreve the memory of the holiday is a token of the hope of heaven which sustains even those who cannot get away.

If we have missed a holiday this year, we shall not grow dull in London; there will be no weariness in the heart which Christ makes his home, with the Father and Their Love. In every Eucharist God says to the faithful toilers, ‘Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will refresh you.’”

In another reflection Congreve addresses the sense of hopes dashed which so often attends the end of the new year holiday. “Why do most of our hopes miss, and only one here and there reach the mark? Why are we always being disappointed by what the year brings us? Is it that we are too bold hoping for good?” Emphatically not:

Disappointment sums up human experience not because we hoped too much, and for things too high above our reach, but because, being created for the sphere of the Eternal Good, we were content to hope for the good things which belongs to the sphere of things that perish. It is this lower sphere of created being that is always failing us.”

Hope will fail if it is focused on “some limited possible good”, but it will be fulfilled when each thing of this world is understood as “a link in a chain by which we reach God Himself at last.”

One of Congreve’s great themes is the hope which is shown to us when contemplating natural beauty we are led on from the created thing to the Creator. Lament for him is a step on the way to refreshment in the sign of God. Congreve expressed this in some of his loveliest writing in a meditation on sunset over the sea seen from Robben Island, the prison, asylum and leper colony off Cape Town where he had a short retreat and break:

a flight of curlews passed me with their wild cry, out of the dark into the dark. The sea made its perpetual moan, uttering the burden of the endless sorrow of a world that cannot rest until man is restored to God. I was conscious of this sorrow of the world everywhere – in the lingering traces of glory departed in the West, in the presence of the unmoving cloud masses, in the cry of the wild birds, and in the voices of the sea far and near. But I knew that sorrow can never be the whole meaning of nature. With all the solemnities of the close of day out at sea, there falls a majestic sadness everywhere; but why do I submit to its influence, and seek the Fellowship of its pain? Why do I listen so hungrily to catch the burden of the breaking waves? To drink the sorrow of the fading light, and the passion of the evening star? Who ever turned to sorrow for sorrow’s sake? I find that there is always woven into the sorrow of nature a joyful mystery, which, if it is ever named by men, is called beauty, or love, or praise. If I strain my ear to listen to the sorrow of the sea, it calls me far away from myself, and all that is base, on into this sphere of the infinite, to hear the music of eternity.”

This is what we have to show for our holiday, when it has led us to God: the transfiguration of lament to joy.

Luke Miller is Archdeacon of London. As Faith & Belief Sector lead for London Resilience, he has been involved in many of the major incidents in the capital over the last few years and the pandemic response and has been appointed a member of the London Recovery Board. He was appointed a Chaplain to the Queen in 2020. You can get your copy of A Life-Long Springtime here.